Freedom Rescinded, Freedom Reclaimed: Part One

Sharecropper Deceptions, Technocratic Neo-Apartheid, and the Continuity of Racial Domination

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the historical and structural continuity between post-emancipation systems of racialized labor exploitation—particularly sharecropping and convict leasing—and contemporary forms of racialized containment embedded in Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) and Technocratic Neo-Colonialism (TNC). Drawing from historical records, oral histories, and critical scholarship, it argues that sharecropping was not a transitional step toward freedom, but a calculated rebranding of slavery through legal contracts, economic dependency, sexual violence, and criminalization. Modern technocratic systems replicate these mechanisms through data extraction, surveillance, predictive policing, and conditional economic programs that erode Black autonomy. The essay proposes the TRRR Framework (Technological, Relational, Resource, and Rights-Based Reconstruction) as a strategic model for building independent infrastructures and securing genuine liberation. Emphasizing memory, spirit, and truth, the paper contends that freedom must be actively reclaimed through innovative yet rooted reconstruction—not passively accepted within systems structured to limit it.

Keywords:

Sharecropping, Technocratic Neo-Apartheid, Technocratic Neo-Colonialism, Reconstruction, Black Autonomy, Convict Leasing, Mass Incarceration, Decolonial Technologies

Preface

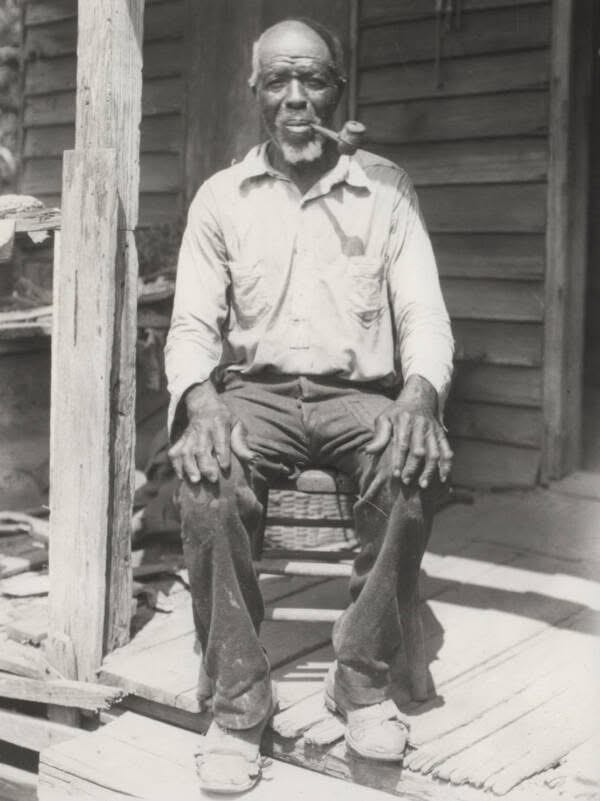

When my father was researching and documenting our family's history, there were stories he did not tell me directly, and others he never wrote down. Yet I heard them nonetheless. They surfaced in the spaces between words, in lingering silences, in glances cast to the side when certain memories stirred too much pain. They were the stories of the so-called sharecroppers of our lineage, including my grandfather. Stories of contracts that wove sexual coercion into their very terms, of women and girls made collateral for debts that were never meant to be repaid. Stories of restricted movement, where leaving a plantation without written permission could bring violence, arrest, or disappearance. Stories of children subjected to endless servitude because their parents’ debts had been structured to be permanent. Stories of rental agreements for farm equipment and work animals that, hidden in their clauses, granted landlords sexual access to the bodies of the vulnerable. And there were worse stories still—stories too painful, too dangerous, or too heavy to fully recount.

My father heard these stories, and he held them. He held them as a griot, a living keeper of memory, as a vessel for the truths too raw for easy telling. He bore them in the hollows of his chest and the quiet spaces of his mind, carrying the burden of knowing without the luxury of forgetting. Some stories he could not bring himself to tell. Some he might not have wanted to, or perhaps they were simply too heavy, too disfigured by suffering, to fit within the frame of speech or page.

I watched him carry them, and I understood that bearing witness is its own kind of work. It, too, leaves its mark and takes its toll.

As a witness, my shoulder was prepared to hold the weight he could no longer name. I stood beside him in the graveyards, helping to steady the tape recorder when it jammed in the middle of an interview, lifting the umbrellas to shield the elders from the sun as they whispered or wept their remembrances. I took the photographs of broken gravestones, carefully organized the rubbings into folders, catalogued dates and names that would otherwise dissolve into dust. These acts were small beside the enormity of what was being entrusted, but they mattered. They were acts of reverence for a lineage that refused to forget, even when forgetting might have been easier.

The work of remembering, the work of truth-telling, has always exacted a toll. It did then, and it does now. And yet it is our inheritance and our obligation.

Today, the forces that once sought to erase us are at it again—but with tools and strategies and technologies they have never had before. Systems of containment and exploitation have evolved; their weapons are faster, more invisible, and more intricately woven into the fabric of daily life. Yet some things have not changed. We still hold a power they will never understand nor conquer: the power of spirit, the power of memory, and the unbreakable power of truth.

This article stands in that lineage. It is a continuation of the work my father undertook with his hands and heart. It is an offering of witness and a refusal of forgetting.

Introduction

W.E.B. Du Bois famously wrote that after emancipation, "The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery" (Du Bois, 1935, p. 30). His observation captures not merely the betrayal of Reconstruction but a recurring pattern in American history: systems of racial domination rarely vanish—they mutate. In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, sharecropping emerged as the new face of racial subjugation. Though framed as a voluntary economic partnership, sharecropping trapped millions of Black Americans in cycles of debt, dependency, violence, and exploitation that mirrored, and in many respects deepened, the conditions of chattel slavery. Legal contracts masked profound coercion; economic “partnership” concealed economic extraction; and claims of freedom obscured brutal social realities.

Today, we face a hauntingly familiar evolution of this pattern: Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) and Technocratic Neo-Colonialism (TNC). Under TNA, domestic systems of digital control, surveillance, and economic management have reconfigured racial hierarchies within national borders. Under TNC, global technological hegemony enables the extraction of labor, data, resources, and sovereignty from marginalized nations and peoples. Programs that appear to uplift Black communities—such as increased funding to Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), minority entrepreneurship initiatives, and technological inclusion projects—often carry hidden costs: the erosion of economic, legal, and cultural autonomy. Just as sharecropping legally rebranded slavery while preserving white supremacy, today’s technocratic policies risk reinscribing structural subordination under the guise of opportunity and inclusion.

This essay examines how sharecropping functioned not as an end to slavery but as its legal, economic, and psychological mutation. By tracing the mechanisms of debt peonage, contractual exploitation, racial violence, sexual coercion, and the criminalization of Black labor through convict leasing, it will establish the historical blueprint for today's technocratic strategies of containment and control. It further argues that recognizing these continuities is essential to resisting modern TNA and TNC structures—and that true liberation demands proactive, independent reconstruction, framed here through the TRRR model: Technological, Relational, Resource, and Rights-Based Reconstruction. History demonstrates that without structural autonomy, every apparent "gain" can be weaponized against those it claims to serve.

II. From Emancipation to Ensnarement: The Broken Promise of Freedom

The end of the Civil War ushered in profound hope among the formerly enslaved population. Freedom, long dreamt of and fought for, seemed within reach. However, the collapse of the Confederacy did not dismantle the social and economic structures that had sustained slavery; rather, it forced them into new forms. The pivotal betrayal came swiftly: in early 1865, General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15, which promised to redistribute approximately 400,000 acres of confiscated Confederate land to newly freed Black families ("forty acres and a mule") (Foner, 1988). Yet by the end of that year, President Andrew Johnson, seeking to restore political relations with Southern elites, overturned these promises. Former Confederates regained their plantations through presidential pardons, and freedpeople were forcibly removed from lands they had begun to settle.

The withdrawal of federal protection and the restoration of white landownership set the stage for the emergence of Black Codes—laws designed to regulate Black labor and behavior with the explicit intent of preserving a racial caste system. As Leon Litwack (1979) noted, "The Black Codes made it clear that, although slavery was dead, the status of Black Americans was to be little better than that of serfs." In states like Mississippi and Alabama, laws criminalized vagrancy, defined narrowly enough to ensnare any Black person found without a white employer's written certification of employment (Foner, 1988). Black citizens who failed to meet these requirements could be fined, imprisoned, or "hired out" to private employers, thus initiating new forms of involuntary servitude.

It is within this legal and economic context that sharecropping took hold. Unable to access land ownership and systematically excluded from political and financial power, freedmen were forced into arrangements with former slaveholders, now relabeled as landlords. The early sharecropping contracts, many of which are preserved in Freedmen’s Bureau records, reveal an imbalance of power that echoes antebellum dynamics. In one 1867 North Carolina contract, a freedman named Virgil Bridges agreed to work the landowner's fields, splitting two-thirds of the crop while submitting to strict limitations: he could not leave the land without permission, was bound to obey all directives from the landowner, and could be penalized for disobedience through forfeiture of wages (Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1867).

Although presented as a labor agreement between nominal equals, the structure of sharecropping fundamentally reproduced the plantation system’s dependencies and vulnerabilities. As Du Bois (1935) would later observe, the freedman “was free in name but a slave to debt and to the caprice of the landlord.” Legal freedom thus coexisted with material and social domination, a contradiction that would shape Black life in the South for generations.

Despite the veneer of contract-based freedom, the structural realities of sharecropping ensured that Black labor remained as exploitable as it had been under slavery. Sharecropping contracts consistently reflected deep asymmetries of power. They mandated not only the division of crops but also strict behavioral regulations: Black families were often prohibited from selling their portion of the crop independently, required to purchase supplies exclusively from landowner-approved merchants, and forbidden from leaving the plantation without written consent. Violation of these terms could result in eviction, forfeiture of the season’s labor, or prosecution under vagrancy laws (Litwack, 1979; Foner, 1988).

One illuminating example appears in the 1868 labor contract between freedman Jesse Jackson and plantation owner William H. White in Mississippi. Under the terms of the agreement, Jackson’s family was obliged to cultivate cotton exclusively, purchase all necessities from White's store at interest rates exceeding 25 percent, and seek permission for any travel off the property. At settlement, White reserved the right to deduct debts and “damages” assessed solely at his discretion (Freedmen's Bureau Records, 1868). Jackson's case was typical rather than exceptional. Sharecropping contracts codified a form of economic bondage, where theoretical rights were undercut by material dependence and legal inequities.

Freedmen’s Bureau officials, tasked with overseeing labor relations during Reconstruction, initially intervened to regulate labor contracts and protect Black workers from the most egregious abuses. In some regions, Bureau agents annulled unfair contracts or facilitated collective bargaining between freedpeople and planters. However, as the federal commitment to Reconstruction waned, Bureau offices became understaffed, undermined by local white hostility, and increasingly ineffective. Historian Eric Foner (1988) observed that “the Bureau’s weakness reflected not merely the hostility of Southern whites but the ambivalence of the federal government toward Black autonomy.”

Even when freedpeople organized to resist exploitative arrangements, they encountered overwhelming obstacles. Black agricultural workers staged strikes, refused to sign oppressive contracts, and petitioned the Bureau for redress. In one 1866 letter from Louisiana, a group of freedmen pleaded for assistance, stating, “We cannot live if we are always in debt to the white man. We ask for our own land and our own rights as free men” (Freedmen’s Bureau Correspondence, 1866). Their appeals, however, often went unanswered or were met with violent reprisals from white planters determined to restore a captive labor force.

The economic architecture of sharecropping operated not simply as a temporary compromise between planters and freedpeople but as a calculated reimposition of racial domination through contractual forms. As W.E.B. Du Bois (1935) asserted, the essential problem was that “the South, having lost slaves, must enslave free men by law and custom.” The failure of Reconstruction to secure Black landownership or enforce equitable labor rights allowed sharecropping to entrench a new system of racial apartheid, one maintained by the simultaneous deployment of law, violence, and economic deprivation.

This reconfiguration of slavery into nominally “free” labor relations set a critical historical precedent for what is now recognized as Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA). In both historical and contemporary forms, the essential strategy remains the same: to constrain the autonomy of a racialized underclass through legal mechanisms that preserve a facade of fairness while ensuring continued subordination. Understanding sharecropping as an early prototype of TNA clarifies the continuity between past and present systems of racial management—and underscores why surface reforms, absent structural transformation, ultimately reinforce the status quo.

III. Mechanics of Exploitation: Debt, Dependency, and Punishment

While sharecropping was presented as a form of economic partnership, it was, in fact, structured to sustain the dependency and dispossession of Black laborers. The apparatus that supported it—the crop-lien system, extortionate credit arrangements, fabricated debts, and legalized coercion—created an economic order in which freedom existed only on paper. Sharecropping bound Black families not only to the land but also to a predatory economic system from which escape was nearly impossible.

At the heart of this system was the crop-lien arrangement. Sharecroppers typically received advances in the form of food, clothing, seed, and tools from landlords or local merchants at the beginning of each planting season. These goods were not offered freely; they were provided on credit, secured by a lien against the upcoming harvest. Interest rates routinely ranged from 20 to 50 percent annually, and prices for goods were artificially inflated to maximize dependency (Foner, 1988; Litwack, 1979). Upon harvest, sharecroppers were required to settle their debts before receiving any share of the proceeds. In many cases, even a successful crop yielded no surplus for the laborer after debts, interest, and fabricated charges were deducted.

The result was a form of debt peonage, a self-reinforcing cycle of dependency that could span generations. One sharecropper interviewed during the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Slave Narratives project described it starkly: "We worked for nothing but a piece of hope that never come true. Every year we ended up owing more than we started with" (Federal Writers' Project, 1941). This sentiment was echoed widely among Black families locked into perpetual servitude, their labor extracted under terms that mathematically ensured continued impoverishment.

Landlords manipulated every aspect of the system to their advantage. Sharecroppers were often required to settle their accounts at the planter's store, where bookkeeping was opaque, and disputes were decided solely by the owner. It was not uncommon for landowners to falsify account books, inflate debts, or withhold proceeds entirely under the claim that the crop's value was insufficient to cover the advances. As Edward Baptist (2014) argues, "planters learned to use credit as a whip"—a tool that replaced the physical lash with economic bondage no less brutal in its effects.

The mechanisms of control extended beyond mere economic manipulation. Travel restrictions written into labor contracts made it illegal for sharecroppers to leave the land without permission. Those who violated these terms risked eviction, arrest, or physical assault. Vagrancy laws passed throughout the South criminalized unemployment and unauthorized movement, providing sheriffs and landowners with legal cover to detain or re-enslave Black workers who attempted to flee exploitative conditions (Blackmon, 2008).

Punishment for perceived infractions was swift and violent. Freedmen’s Bureau records document countless cases where Black laborers were whipped, beaten, or imprisoned at the whim of white landowners. In one Louisiana case from 1867, a sharecropper was severely beaten for visiting his sick wife without the landowner’s permission, resulting in permanent injury (Freedmen's Bureau Correspondence, 1867). Despite the Bureau’s theoretical authority, few perpetrators were punished, and local law enforcement often colluded with planters to suppress Black mobility and dissent.

This coordinated system of debt manipulation, physical coercion, and legal oppression reveals the falsity of the narrative that sharecropping represented a step toward Black economic autonomy. Instead, as W.E.B. Du Bois (1935) emphasized, it was a calculated redesign of racial capitalism—a system in which "the ownership of land, the power of credit, the control of the law, and the force of violence were mobilized against the Black worker" (p. 120).

Seen in this light, sharecropping was not simply an economic arrangement; it was an integrated regime of racial control. Debt became a weapon more efficient than chains, constraining Black life within a framework that offered no real possibility of advancement. In every meaningful way, sharecropping replicated the plantation economy’s logic of maximum extraction with minimal obligation, wrapped in the legal fictions of free labor and contractual choice.

This historical structure serves as a direct precursor to the dynamics of Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) today. Just as sharecropping contracts ensnared Black families through debt mechanisms hidden beneath a facade of legality, modern systems of predatory lending, surveillance-based policing, conditional public assistance, and "opportunity programs" replicate the architecture of dependency and limited mobility. These continuities are not coincidental; they are the legacy of an unbroken strategy of racialized containment and extraction, adapted to the tools and discourses of each successive era.

Understanding the mechanics of sharecropping—its deliberate structuring of debt, dependency, and punishment—provides critical insight into the persistence of racialized economic hierarchies in the contemporary United States. It underscores the necessity of confronting not merely the symptoms of inequality, but the deep systemic designs that have evolved precisely to survive moments of apparent reform.

IV. Physical and Psychological Coercion: Violence, Surveillance, and Control

The success of the sharecropping system in maintaining racialized labor exploitation depended not solely on economic dependency but also on the consistent application of coercive force. In the decades following emancipation, physical violence, psychological intimidation, and the threat of criminalization became essential tools to enforce Black compliance. The plantation’s whip had not disappeared; it had simply adapted, masked by the language of contracts, policing, and private justice.

Immediately after the Civil War, white planters recognized that legal emancipation posed a direct threat to the plantation economy. Freedpeople sought to reunite families, relocate for better opportunities, or negotiate fairer labor terms. Their mobility alone represented a political act, a refusal to remain bound to land and power structures that had enslaved them. As a result, Southern legislatures rapidly passed Black Codes designed to curtail Black freedom of movement and preserve access to cheap labor (Foner, 1988).

Under these codes, "vagrancy" became a criminal offense applied almost exclusively to Black individuals. Any freedperson found without written proof of employment could be arrested, fined, and "hired out" to white employers to pay off their debts—a process virtually indistinguishable from the slave markets they were supposed to have escaped. In Mississippi, for example, the Black Code of 1865 stated that “all freedmen, free Negroes, and mulattoes” without lawful employment could be fined or jailed and, if unable to pay the fine, leased out to labor for any white person willing to pay it (Litwack, 1979).

The criminalization of unemployment and movement functioned hand in hand with private acts of terror. The Ku Klux Klan, founded in 1865, became one of the most potent enforcers of white supremacy during the Reconstruction era. Klan members and other white vigilantes targeted Black sharecroppers who attempted to leave plantations, assert wage demands, organize for better conditions, or simply exercise the basic freedoms guaranteed by law. Lynchings, beatings, house burnings, and night rides became common tools of intimidation, designed to demonstrate that formal emancipation had not shifted the real balance of power (Dray, 2002).

General Carl Schurz, in his 1865 report on conditions in the postwar South, described this reign of terror candidly: "In many instances, Negroes who walked away from plantations, or were found upon the road, were shot or otherwise severely punished" (Schurz, 1865). Freedpeople understood that legal protections offered scant refuge against such violence. Local law enforcement was often indistinguishable from the perpetrators themselves, and federal authorities were too few, too politically compromised, or too reluctant to intervene.

The Freedmen’s Bureau compiled extensive reports of abuses, offering a grim catalog of physical coercion. In Alabama, Fanny Tipton, a freedwoman working under a labor contract, was whipped with thirty lashes by the planter’s son for refusing to clean a rabbit he had killed—an act beyond her assigned agricultural duties (Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1866). In Louisiana, entire Black families were forcibly evicted and assaulted for petitioning for their agreed wages (Foner, 1988). Such cases were not isolated incidents but systemic practices designed to reinforce the vulnerability of Black laborers and punish any assertion of independence.

Importantly, this violence was not only physical but also deeply psychological. The constant threat of eviction, arrest, or bodily harm created a climate of fear that shaped every aspect of Black life under sharecropping. It policed behavior, silenced protest, and rendered even legal "contracts" coercive in practice. A system that relied on the labor of a theoretically free population thus remained dependent on the credible threat of punishment—an economic model only sustainable through terror.

The architecture of control established in the sharecropping South resonates strikingly with the patterns of Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) today. Where whips and rifles once maintained racialized labor hierarchies, modern systems of surveillance, predictive policing, and algorithmic criminalization fulfill similar functions. Programs that disproportionately monitor and police Black communities—often under the banner of "public safety" or "technological efficiency"—operate to suppress mobility, autonomy, and dissent (Alexander, 2010). Just as Black sharecroppers were criminalized for leaving plantations or contesting debt, Black citizens today are criminalized for resisting the structural inequalities embedded in housing, employment, and policing systems.

Contemporary "predictive policing" algorithms, deployed in many American cities, rely on data that already reflects historical patterns of racialized surveillance and arrest. As a result, they disproportionately target Black and Brown neighborhoods, reinforcing cycles of criminalization much as Black Codes once did (Benjamin, 2019). Similarly, modern "risk assessment" tools used in sentencing and parole replicate the racial biases of the historical criminal justice system, ensuring that racial hierarchies persist beneath the surface of ostensibly neutral technologies.

Thus, the psychological and material coercion that underpinned sharecropping has not been relegated to the past. It has been updated, reframed, and retooled to fit the logics of a digital, technocratic society. Surveillance replaces the overseer’s eye. Predictive algorithms replace plantation patrols. Data profiling replaces vagrancy laws. Yet the underlying purpose remains constant: to constrain Black autonomy and ensure the continued extraction of Black labor, creativity, and wealth within a system structured for inequality.

Recognizing the throughlines between historical physical coercion and contemporary digital surveillance is not merely an academic exercise. It is a necessary act of resistance against the evolving strategies of containment and control that seek to obscure their lineage and operate under new names. Just as the sharecropper’s freedom was hollowed out by systems of violence and control, so too must we interrogate the "freedoms" offered within technocratic regimes that rely on surveillance, criminalization, and coercion to maintain racialized social orders.

V. Gendered Dimensions of Exploitation: Sexual Violence and Economic Dispossession

The systemic violence that characterized sharecropping did not affect Black individuals uniformly across gender, nor was it limited to a singular form of subjugation. While all Black laborers endured economic exploitation, racialized surveillance, and physical coercion, all Black persons were also subjected to a pervasive, often concealed form of domination: sexual violence institutionalized through labor relations, debt arrangements, and economic dependency. In the post-Emancipation South, sexual coercion remained a fundamental, albeit frequently suppressed, instrument of racial capitalist control.

During enslavement, the sexual exploitation of Black women and girls served both as a means of individual dominance and a mechanism of economic accumulation. Enslaved women were systematically subjected to rape, coercion, and reproductive control to augment the labor force and gratify the desires of white slaveowners. Although formal emancipation abolished the legal framework of chattel ownership, it did not eradicate the structures or expectations of sexual access to Black bodies. Rather, these practices were incorporated into the emerging sharecropping economy, concealed within contracts, debt arrangements, and informal power hierarchies.

Freedwomen who entered sharecropping agreements frequently found themselves vulnerable to renewed forms of sexual coercion. The material conditions of dependency—including the absence of independent land, financial capital, and legal protection—created circumstances in which white landowners could exploit their economic dominance to demand sexual compliance. Rental agreements for land, tools, and farm animals often entailed implicit expectations of sexual availability, particularly when families incurred debt.

However, these predatory practices were not solely directed at women and girls. A crucial and often deliberately concealed aspect of post-emancipation sexual violence involved the targeting of Black boys, adolescent males, and adult Black men. Debt servitude contracts and labor arrangements, whether formally written or enforced through custom, were sometimes employed to justify and conceal the sexual exploitation of Black males by plantation owners, overseers, and post-emancipation property holders. Debt itself became a pretext not only for forced labor but also for coerced sexual subjugation.

Survivor accounts and concealed testimonies preserved in oral histories suggest that practices of “buck breaking” persisted after emancipation, repurposed within sharecropping and convict leasing economies. In these instances, the rape of Black boys and men was used as a tactic of domination, humiliation, and control—both to traumatize individuals and to terrorize entire communities. The historical record is fragmented, as few victims survived to recount their experiences, and the stigma surrounding male sexual victimization further impeded acknowledgment. Nonetheless, the evidence demonstrates that sexual violence against Black men and boys was not an aberration but rather an extension of racialized exploitation intended to dismantle autonomy and enforce absolute subordination.

The psychological impact of this violence was devastating. Sexual coercion deprived individuals of bodily sovereignty, weaponized shame to discourage resistance, and disrupted communal bonds. It terrorized not only individuals but also entire families and communities, signaling that no one—regardless of gender, age, or status—was beyond the reach of racial domination. It reinforced a system in which Black life was subjected to violation without consequence and to labor extraction without limit.

The case of Loucy Jane Boyd, a fifteen-year-old freed girl raped by her employer in Tennessee, remains one of the few documented instances pursued through intervention by the Freedmen’s Bureau. However, the broader reality was that numerous acts of sexual violence—against women, girls, boys, and men—were never recorded, prosecuted, or acknowledged in the formal historical record. These acts persisted in oral histories, in silences, and in the intergenerational trauma experienced by descendants.

The legacy of gendered exploitation in sharecropping cannot be narrowly interpreted. It was not confined to a binary framework of female victimization and male exemption; it was a comprehensive system of bodily domination across gender lines, designed to neutralize Black agency and perpetuate the racial caste structure. Economic servitude and sexual terror were mutually reinforcing pillars of a broader endeavor: the maintenance of white supremacy through total domination of Black life.

This history resonates into the present through the mechanisms of Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) and Technocratic Neo-Colonialism (TNC). Currently, Black women remain disproportionately targeted by predatory financial systems, undercompensated labor markets, and institutional invisibility. Simultaneously, Black men and boys face systemic criminalization, surveillance, and vulnerability to physical and psychological violence within carceral institutions. Both phenomena reflect a fundamental continuity: the ongoing commodification and violation of Black bodies to sustain racialized economic hierarchies.

Modern initiatives that promise “equity” or “inclusion” often fail to address these historical continuities. They provide conditional opportunity without structural transformation, visibility without sovereignty, and access without protection. They replicate established patterns under new terminology, ensuring that the foundational logics of extraction, dispossession, and violation persist.

Acknowledging the full, gender-inclusive dimensions of sexual violence under sharecropping is not only a matter of historical accuracy. It is a necessary step toward dismantling the silences and distortions that have long obscured the extent of Black suffering—and toward affirming that genuine liberation must confront every form of exploitation, across all individuals, all histories, and all communities.

VI. Slavery by Another Name: Sharecropping, Convict Leasing, and Mass Incarceration

The collapse of Reconstruction and the entrenchment of sharecropping did not mark the final adaptation of racialized labor exploitation. As economic pressures fluctuated, and as freedpeople sought ways to resist the plantation system, Southern elites developed new mechanisms to reassert control—mechanisms that transformed legal emancipation into yet another framework of captivity. Chief among these was the system of convict leasing, a practice that criminalized Black existence and auctioned Black bodies into forced labor under the guise of legal punishment. Through convict leasing, and the broader carceral regimes that followed, slavery did not disappear; it evolved, mutating into new forms that preserved its essential logic while adapting to the constraints of the post-Emancipation legal order.

The legal foundation for this transformation was the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude "except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted" (U.S. Const. amend. XIII, §1). This exception clause created a constitutional loophole through which Southern states engineered the mass re-enslavement of Black Americans by criminalizing behaviors associated with poverty, freedom of movement, and social autonomy. Black Codes and subsequent vagrancy laws made unemployment, loitering, "insulting gestures," and failure to settle debts into criminal offenses, almost exclusively applied to African Americans (Foner, 1988; Blackmon, 2008).

Once arrested, Black men, women, and children were subjected to court proceedings that were cursory at best. Fines and court costs were imposed, and when defendants could not pay—which was often by design—they were "leased" to private employers, including plantations, railroads, mines, and factories. In Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and other former Confederate states, convict leasing became a cornerstone of regional economies. By the 1880s, states like Alabama derived as much as 73 percent of their total state revenue from the leasing of Black convict labor (Blackmon, 2008).

The conditions faced by those caught in the convict leasing system were often worse than those endured under chattel slavery. Employers had no long-term economic investment in the lives of the leased convicts; the death of a worker was a minor inconvenience, not a financial catastrophe. Reports from the period document extreme brutality: prisoners were whipped, starved, overworked, denied medical care, and subject to arbitrary execution. Entire graveyards filled with the bodies of leased convicts, many unnamed and unmourned, dotted the Southern landscape (Oshinsky, 1996).

The transition from sharecropping to convict leasing was not accidental; it was deeply interconnected. Sharecroppers who attempted to leave plantations without paying fabricated debts were often charged with fraud or vagrancy. A family unable to meet their obligations might see their eldest sons—or entire households—swept into the criminal justice system under pretextual charges. In effect, debt and poverty were criminalized, and incarceration became the new enforcement mechanism for racialized labor extraction.

One illustrative case involves the 1898 arrest of Green Cottenham, a young Black man in Alabama, who was sentenced to hard labor for the crime of vagrancy. Cottenham was leased to U.S. Steel, where he labored under inhumane conditions and died within months—one among thousands whose lives were consumed in this brutal reconfiguration of slavery (Blackmon, 2008). His story, though documented, represents only a fraction of the countless, often unrecorded, lives crushed by the convict leasing regime.

The convict leasing system served not only economic but psychological and political purposes. It reasserted white supremacy at a time when Black political participation briefly flourished during Reconstruction. By stripping Black citizens of their freedom, dignity, and bodily autonomy under the color of law, the system reinforced the message that any assertion of independence could be met with swift and devastating reprisal.

The strategies perfected during the sharecropping and convict leasing eras have cast a long shadow over American life. They are embedded within the architecture of the modern prison-industrial complex—a system that, like its predecessors, criminalizes Black life, profits from Black captivity, and sustains racial hierarchies under the guise of legal neutrality (Alexander, 2010). Today, Black Americans are incarcerated at five times the rate of white Americans, a disparity rooted not in contemporary crime rates but in historical patterns of racialized control (The Sentencing Project, 2021).

Mass incarceration represents the direct descendant of the racialized labor systems of the postbellum South. Where sharecropping enforced dependency through debt and contractual fraud, and convict leasing through criminalization and forced labor, the modern carceral state enforces racialized containment through surveillance, policing, mandatory sentencing, and prison labor. As Loïc Wacquant (2002) argues, the ghetto and the prison have become “twin institutions” for the management of Black populations in the United States, preserving social marginalization even as the language of democracy and equality is invoked.

The systems of Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) and Technocratic Neo-Colonialism (TNC) extend these logics into new domains. Algorithmic risk assessments, predictive policing technologies, and digital surveillance infrastructures reinforce racial biases under the guise of scientific objectivity. Meanwhile, prison labor, often paid at pennies per hour, continues to supply industries and services that profit from Black and Brown incarceration—an economic model chillingly similar to the convict leasing practices of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Understanding convict leasing and its transition into modern mass incarceration reveals that slavery, as an institution, was not abolished; it was transmuted. It adapted to new legal frameworks, economic imperatives, and technological tools while maintaining its core function: the control, exploitation, and dehumanization of Black life for economic and political gain. This continuity demands not merely acknowledgment but radical intervention, for without structural transformation, the machinery of racial capitalism will continue to evolve and entrench itself deeper within the fabric of modern society.

VII. The Illusion of Advancement: Technocratic Trap for Black Institutions and Communities

In the contemporary era, efforts to uplift Black communities through investments in education, entrepreneurship, and technology have gained widespread attention. Initiatives to increase funding for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), promote minority-owned businesses, and expand access to digital technologies are frequently presented as evidence of societal progress. However, a deeper examination reveals a troubling continuity with historical patterns: these programs often replicate the dynamics of racial control masked as opportunity, reinforcing dependency, extracting value, and stripping autonomy in ways that mirror the evolution of sharecropping and convict leasing systems.

The rise of Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) and Technocratic Neo-Colonialism (TNC) provides a critical lens through which to understand these developments. Under TNA, Black communities are domestically contained and managed through systems that offer visibility without power, participation without ownership, and inclusion without genuine autonomy. Under TNC, similar strategies are deployed globally, as marginalized nations are drawn into development projects that extract their resources, labor, and data while offering limited, conditional benefits.

Recent federal initiatives targeting HBCUs provide a revealing case study. While increased funding, research grants, and partnerships with major corporations are publicly celebrated, these investments often come attached to standardization requirements, intellectual property concessions, and strategic influence over institutional curricula and priorities. Rather than empowering HBCUs to define independent educational and research agendas rooted in Black liberation and innovation, many funding programs incentivize alignment with corporate and governmental frameworks that serve broader technocratic interests (Gasman & Commodore, 2014).

This process mirrors the false autonomy granted to Black sharecroppers following emancipation. Just as sharecroppers were nominally "free" to contract their labor while being systematically trapped in debt and dependency, Black institutions today are encouraged to participate in competitive funding ecosystems that structurally limit their autonomy. Funding streams often favor projects that align with technocratic priorities—such as STEM research tied to defense industries, data-driven educational technologies, or entrepreneurship models reliant on venture capital—while marginalizing initiatives centered on Black historical preservation, radical political thought, or community-based economics.

Moreover, the datafication of Black educational spaces introduces new forms of extraction. Partnerships with technology companies frequently involve the collection of student data, intellectual property rights over research outputs, and the commodification of institutional reputations for corporate branding purposes. In exchange, HBCUs receive access to resources that, while valuable, often leave them more entangled within structures they do not control. This mirrors the plantation economy’s reconfiguration after emancipation: Black labor and knowledge are harvested for the benefit of broader systems, while the institutions themselves remain financially precarious and structurally subordinate.

Similar dynamics are evident in programs promoting minority entrepreneurship. Grants, competitions, and incubator initiatives promise to empower Black entrepreneurs, yet they often impose models of success that are extractive, risk-laden, and disconnected from community-based traditions of cooperative economics and collective ownership. Participants are encouraged to pursue individual success within capitalist frameworks rather than building resilient, independent economic ecosystems that challenge systemic inequities (Gordon Nembhard, 2014). The result is a replication of sharecropping’s fundamental logic: dependency on external capital, vulnerability to predatory practices, and containment within structures that ultimately serve technocratic elites.

These strategies are not incidental; they are deliberate evolutions of historical patterns of racial management. In each phase—sharecropping, convict leasing, mass incarceration, and now technocratic "empowerment"—the central goal remains the same: to extract value from Black labor, culture, and creativity while denying full autonomy, political agency, and economic independence. The language has changed; the mechanisms have become more sophisticated; but the structural realities endure.

The illusion of advancement without structural change is particularly dangerous because it blunts critical resistance. Appearances of progress—new buildings on HBCU campuses, rising numbers of minority-owned businesses, greater representation in elite institutions—can obscure the persistent systemic vulnerabilities that undergird these achievements. Without independent control over land, resources, data, intellectual property, and governance, Black institutions remain vulnerable to shifts in political winds, market fluctuations, and technocratic agendas they do not set.

The parallels to historical sharecropping are unmistakable. Then, as now, Black participation in economic systems was conditioned on compliance with terms set by those who controlled capital and law. Then, as now, the promise of upward mobility masked the reality of structural dependency. Then, as now, the autonomy necessary for genuine liberation was denied through a combination of legal, economic, and psychological controls.

Recognizing these continuities is critical for developing strategies of resistance and reconstruction. It demands a refusal to accept surface-level inclusion as sufficient. It requires insisting on ownership rather than access, sovereignty rather than visibility, and liberation rather than partnership under unequal terms. Without this clarity, Black communities risk becoming further entrenched in cycles of managed dependency that mirror the very systems from which they seek freedom.

The work ahead must involve not merely participation in technocratic frameworks but their radical reimagining—or their complete replacement. Black institutions must move toward models of Technological, Relational, Resource, and Rights-Based Reconstruction (TRRR) that prioritize structural autonomy, community-centered innovation, and resistance to the ongoing commodification of Black life. As history teaches, the failure to build independent structures leaves freedom perpetually vulnerable to betrayal.

VIII. TRRR Framework: Building True Liberation Beyond Technocratic Control

The historical arc from emancipation through sharecropping, convict leasing, and mass incarceration reveals an unmistakable lesson: systems of racial domination do not vanish; they adapt, evolve, and reassert themselves under new guises. Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) and Technocratic Neo-Colonialism (TNC) represent the latest manifestations of this evolution, harnessing digital technologies, data infrastructures, and algorithmic governance to entrench inequalities that once wore the open mask of racial apartheid.

To resist these systems—and to build structures of true liberation—requires a paradigm shift: not mere participation within technocratic frameworks, but the construction of autonomous ecosystems grounded in historical memory, cultural sovereignty, and technological innovation wielded in service of freedom.

The TRRR Framework—Technological, Relational, Resource, and Rights-Based Reconstruction—offers a strategy for this work. It is not a call for nostalgic return but for insurgent innovation: the reappropriation of tools we were never meant to control, the forging of alliances across fragmented communities, and the codification of rights and resources outside the grasp of predatory systems.

Technological Reconstruction: Building Independent Infrastructures

Technology has historically been used to surveil, discipline, and extract from Black communities. It must now be repurposed as a tool of sovereignty. This requires moving beyond mere consumption—beyond owning devices or utilizing platforms designed by others—toward ownership of the infrastructures themselves.

Decentralized technologies, particularly blockchain, offer possibilities for constructing systems of recordkeeping, land registration, mutual aid coordination, and economic exchange that are resistant to centralized control. Blockchain-based land registries, for example, could be used to secure community land holdings against predatory development, ensuring transparency and collective ownership. Smart contracts could automate the distribution of cooperative funds, reducing dependency on banks or philanthropic intermediaries historically weaponized against Black autonomy.

Similarly, the careful, sovereign development of AI systems—trained on community-controlled data and designed to serve emancipatory rather than extractive ends—could provide powerful tools for education, healthcare, legal advocacy, and cultural preservation. AI should not be accepted wholesale from systems built to surveil and exclude; it must be radically reimagined, developed in alignment with Black epistemologies, ethical frameworks, and community needs.

Technological reconstruction demands mastery, not mimicry: the deep study of technical tools with the explicit goal of deploying them in defense of freedom rather than in service of surveillance and exploitation.

Relational Reconstruction: Forging Global and Local Alliances

Historically, Black resistance movements have drawn strength from relational webs that transcended geography: from maroon communities in the Americas to pan-African networks in the twentieth century. Today's technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to rebuild and expand these networks—but doing so requires intentionality.

Decentralized communication infrastructures—encrypted peer-to-peer platforms, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) for mutual aid and governance—can support cross-border alliances unmediated by hostile state apparatuses or surveillance-capitalist platforms. Diasporic communities can collaborate on land acquisition, resource pooling, political education, and emergency response, building resilience against the global pressures of TNC.

Relational reconstruction also requires local commitments: strengthening community councils, revitalizing independent Black institutions, and fostering intergenerational knowledge transmission. Technology must serve as a facilitator of these relationships, not a substitute for them.

Solidarity must be relational, not transactional; dynamic, not extractive; principled, not opportunistic.

Resource Reconstruction: Securing Economic Autonomy

Without control over resources, freedom remains aspirational.

The plantation, the sharecropping system, the prison—all have been animated by the extraction of Black labor and the theft of Black-created wealth.

Resource reconstruction demands collective strategies for economic independence:

Land trusts and cooperatives insulated from speculative markets.

Cooperative businesses owned and governed by Black workers and communities.

Digital currencies and decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystems oriented toward mutual aid and long-term community investment rather than speculative accumulation.

Reclamation and protection of intellectual property and cultural production, preventing the continued extraction of Black creativity by technocratic industries.

Technology can support these efforts—but only if deployed within ethical frameworks that reject the logics of extractive capitalism. Blockchain technology can anchor transparent cooperative economies. AI tools can optimize resource distribution and identify opportunities for land acquisition, grant access, and mutual aid expansion.

Resource reconstruction is not about access to capital; it is about building autonomous economic engines capable of sustaining resistance across generations.

Rights-Based Reconstruction: Codifying and Defending Autonomy

Throughout history, rights granted by external systems have proven fragile at best and lethal at worst. Black communities must move toward the codification and defense of rights outside the recognition of hostile states and predatory corporations.

Technological tools offer new possibilities for this work: decentralized identity platforms, smart contracts encoding community governance agreements, blockchain-based archival systems preserving historical claims, and encrypted advocacy networks resistant to infiltration.

Rights must be understood not as privileges granted by dominant systems but as inalienable inheritances anchored in historical memory and communal will. Rights-Based Reconstruction demands frameworks for:

Community self-defense.

Cultural preservation and reclamation.

Educational autonomy.Environmental stewardship tied to ancestral relationships with land.

It demands the radical assertion that our sovereignty does not depend on their permission.

IX. Freedom Rescinded, Freedom Reclaimed

The history of Black life in the aftermath of American slavery reveals a brutal truth: systems of racial domination do not disappear when exposed or legally abolished; they evolve, adapt, and reconstitute themselves in new forms. Sharecropping, convict leasing, mass incarceration, and the emerging architectures of Technocratic Neo-Apartheid (TNA) and Technocratic Neo-Colonialism (TNC) form an unbroken chain, a shifting set of strategies designed to contain Black freedom while extracting Black labor, creativity, and life.

What was offered after emancipation was not true freedom but a conditional reprieve—a brief moment in the sun, followed by the reimposition of subjugation through economic dependency, legal manipulation, physical coercion, and psychological terror. Sharecropping did not represent a step toward liberation; it rebranded enslavement in contractual terms. Convict leasing did not punish criminality; it criminalized Black existence to feed economic systems of forced labor. Mass incarceration did not arise organically; it grew from soil already fertilized by centuries of racialized control. And today's technocratic systems of inclusion and empowerment—if not critically interrogated and radically reimagined—threaten to reproduce these dynamics beneath new banners and new tools.

The technologies now deployed in the name of progress—algorithmic governance, predictive policing, biometric surveillance—are not neutral. They inherit the designs and imperatives of the structures they emerge from. Their sophistication only masks the persistence of old hierarchies, refining the management of inequality rather than dismantling it. This historical continuity demands more than acknowledgment; it demands action grounded in historical understanding, strategic innovation, and unwavering commitment to autonomy.

Freedom has never been given; it has only ever been seized, cultivated, and defended. The work ahead is not merely to participate in existing systems but to build new ones: technological, economic, social, and cultural architectures that are rooted in our histories, responsive to our present realities, and oriented toward our future sovereignty.

The TRRR Framework—Technological, Relational, Resource, and Rights-Based Reconstruction—is not a final blueprint but a beginning. It offers a foundation for constructing independent infrastructures, revitalizing global and local solidarities, securing economic autonomy, and codifying inalienable rights beyond the reach of predatory systems. It demands that we not merely demand inclusion, but insist upon liberation.

We must remember that the forces arrayed against Black autonomy today are armed not only with money and machines but with the legacy of centuries of unbroken practice in domination. They have new tools, but their goals are old.

Yet we too inherit a legacy: the legacy of those who survived when survival was not meant to be possible; those who built when building was forbidden; those who remembered when forgetting would have been easier.

We have the power of spirit.

We have the power of memory.

We have the power of truth.

And through deliberate, courageous reconstruction, we can wield the tools of this age—not as their servants, but as their remakers.

Freedom must be reclaimed, not offered.

This is the work.

This has always been the work.

And it begins again—now.

References

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press.

Baptist, E. E. (2014). The half has never been told: Slavery and the making of American capitalism. Basic Books.

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim Code. Polity Press.

Blackmon, D. A. (2008). Slavery by another name: The re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Anchor Books.

Camp, S. M. (2004). Closer to freedom: Enslaved women and everyday resistance in the plantation South. University of North Carolina Press.

Dray, P. (2002). At the hands of persons unknown: The lynching of Black America. Random House.

Federal Writers' Project. (1941). Slave narratives: A folk history of slavery in the United States from interviews with former slaves. Library of Congress.

Foner, E. (1988). Reconstruction: America’s unfinished revolution, 1863–1877. Harper & Row.

Freedmen’s Bureau Records. (1865–1872). Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands. National Archives and Records Administration.

Gasman, M., & Commodore, F. (2014). Opportunities and challenges at historically Black colleges and universities. New Directions for Higher Education, 2014(165), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20083

Glymph, T. (2008). Out of the house of bondage: The transformation of the plantation household. Cambridge University Press.

Gordon Nembhard, J. (2014). Collective courage: A history of African American cooperative economic thought and practice. Penn State University Press.

LeFlouria, T. (2015). Chained in silence: Black women and convict labor in the new South. University of North Carolina Press.

Litwack, L. F. (1979). Been in the storm so long: The aftermath of slavery. Vintage Books.

Litwack, L. F. (1998). Trouble in mind: Black southerners in the age of Jim Crow. Vintage Books.

Oshinsky, D. M. (1996). Worse than slavery: Parchman Farm and the ordeal of Jim Crow justice. Free Press.

Painter, N. I. (1996). Sojourner Truth: A life, a symbol. W. W. Norton & Company.

Schurz, C. (1865). Report on the condition of the South. U.S. Senate Executive Document No. 2, 39th Congress, 1st Session.

The Sentencing Project. (2021). Report to the United Nations on racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/report-to-the-united-nations-on-racial-disparities/

U.S. Const. amend. XIII.

Wacquant, L. (2002). From slavery to mass incarceration: Rethinking the “race question” in the US. New Left Review, 13, 41–60.

Wacquant, L. (2001). Deadly symbiosis: When ghetto and prison meet and mesh. Punishment & Society, 3(1), 95–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/14624740122228276